Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are related chronic inflammatory autoimmune conditions but differ in the tissue affected. In psoriasis, the inflammation is directed toward the skin. In psoriatic arthritis, the inflammation is directed toward the joints, similar to rheumatoid arthritis, causing inflammation (swelling, redness, pain and stiffness) and damage. Like any autoimmune condition, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis can manifest from mild to severe disease. There is a relationship between the severity of skin disease and arthritic involvement but they do not always correlate. Some patients may have severe skin disease and no arthritis and some arthritis patients may have only minimal skin disease.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis causes cells to build up rapidly on the surface of the skin, forming thick, silvery scales and itchy, dry, red patches that are sometimes painful. It can also affect the nails, leading to thickened, pitted or ridged nails or the joints, leading to swollen and stiff joints. This condition is known as psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriasis patches can range from a few spots of dandruff-like scaling to major eruptions that cover large areas. Most types of psoriasis go through cycles, flaring for a few weeks or months, then subsiding for a time or even going into complete remission.

The cause of psoriasis isn’t clear, but it’s thought to involve an immune system dysfunction involving immune cells (lymphocytes) called T cells. In psoriasis, the T cells attack healthy skin cells by mistake, as if to heal a wound or to fight an infection.

Researchers have found genes that are linked to the development of psoriasis, but as in most autoimmune conditions, environmental factors probably play a larger role. There are a number of environmental factors that may trigger psoriasis including:

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory arthritis affecting the joints that typically occurs in people with skin psoriasis, but it can occur in people without skin psoriasis, particularly in those who have relatives with psoriasis. In some people, it is mild, with just occasional flare ups. In other people, it is continuous and can cause joint damage if it is not treated.

Psoriatic arthritis typically affects the large joints, especially those of the lower extremities, distal joints of the fingers and toes, and also can affect the back and sacroiliac joints of the pelvis. Although the disease usually isn’t as crippling as other forms of arthritis, it can cause stiffness and progressive joint damage that can lead to permanent deformity. Psoriatic arthritis is sometimes misdiagnosed as gout, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis.

A comprehensive approach to the management of complex conditions such as autoimmune disease must take into consideration many aspects of health, including gut barrier integrity and imbalances of gut flora, liver detoxification capacity and toxic burden, hormone imbalances, energy production capacity, nutrient status and most importantly, immune imbalances which promote autoimmune states. More specifically, Functional Medicine approaches autoimmune disease by identifying the triggers and mediators of the autoimmune attacks, minimizing the self-destructive immune responses and enhancing the body’s ability to recover from flare-ups.

There are 4 areas of management of autoimmune conditions in the Functional Medicine approach:

Lab testing is a critical first step in identifying the extent of systemic inflammation and ruling out many environmental insults which act as triggers and mediators of autoimmunity, such as chronic infection, heavy metal toxicity and decreased capacity to perform liver detoxification. Food sensitivities can also promote inflammation and potentially drive autoimmune responses. Identifying and addressing these issues is critical in autoimmune patients to minimize damage and promote restorative function.

Functional Medicine addresses diet and lifestyle issues as well as using anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating herbs and nutritional compounds to decrease immune responses to self-tissue. Identifying the triggers of autoimmunity and modulating the immune response can have powerful long-term positive effects on slowing or stopping tissue destruction and improving quality of life.

There are a number of natural compounds that help support a faster recovery by breaking down offending triggers, increasing blood flow to target tissue, and dampening the immune response.

Addressing Associated Conditions and Promote Autoimmune Responses

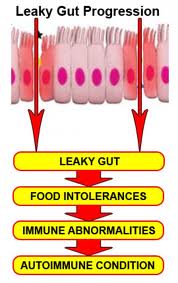

Addressing Associated Conditions and Promote Autoimmune ResponsesThere is growing evidence that increased intestinal permeability plays a pathogenic role in various autoimmune diseases. Increased intestinal permeability and compromised gut integrity appears to precede AI disease and predisposes to immune activation and chronic inflammation. Assessment and proper restoration of the integrity of the intestinal barrier is crucial in managing autoimmune conditions. Read More on Leaky Gut

There is growing evidence that increased intestinal permeability plays a pathogenic role in various autoimmune diseases. Identifying the existence of intestinal permeability and addressing this condition, leads to a more comprehensive and satisfactory outcome in the autoimmune patient.

Milpitas: 408-262-6606

1649 S. Main Street, Ste. 102

Milpitas, CA 95035

Oakland: 510-350-8082

6232 La Salle Ave

Oakland, CA 94611