In this segment and subsequent segments in this series, we examine common disorders of the primary organs of the GI tract, including the stomach, small intestine and colon. The focus of this segment and the next segment is common disorders of the stomach. We start by examining a very common condition that often gets overlooked in conventional medicine but underlies various stomach conditions and results in a wide range of stomach symptoms.

Hypochlorhydria

Hypochlorhydria

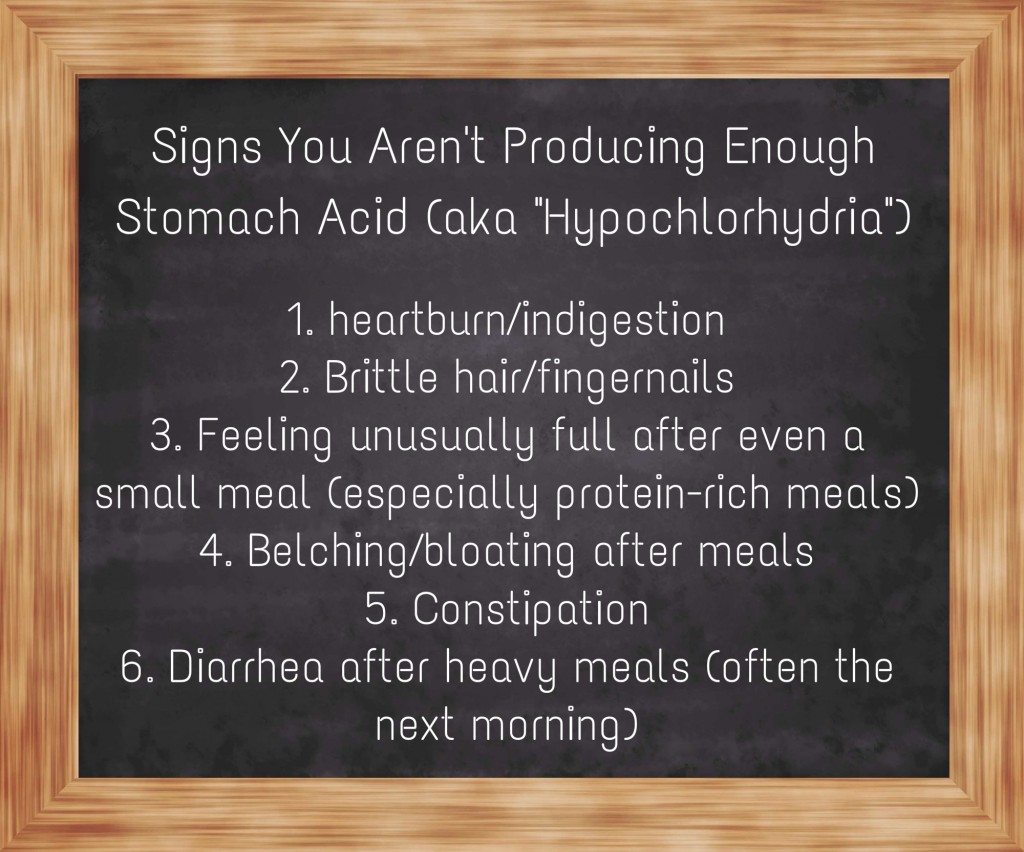

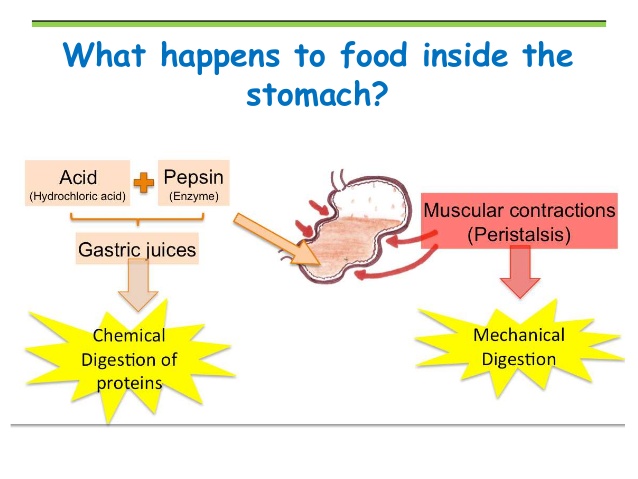

As described in the section Functions of Gastrointestinal Tract, the stomach receives the food from the esophagus where it meets with stomach enzymes which aid in protein digestion before emptying into the duodenum. The stomach acid sanitizes the bolus that enters the stomach and forms chyme. When the chyme enters the small intestine, it is highly acidic, until it mixes with the bile in the duodenum which makes the chyme more alkaline. The primary stomach enzymes used in protein digestion are hydrochloric acid (HCl) and pepsin. A healthy stomach secretes 2-3 liters of gastric juice per day! But this is not the case with many people in today’s modern world. Many people suffer from a problem of under secretion of these gastric enzymes (a common condition called hypochlorhydria). This is especially common in the elderly.[86] This can lead to incomplete protein digestion which can result in a host of health problems, including symptoms such as gas, bloating, burping after meals, difficulty swallowing pills and almost any type of digestive difficulty. As we will see later on this page, it is the primary cause of acid reflux and heartburn as well.

Symptoms of Hypochlorhydria:

Symptoms of Hypochlorhydria:

- Gas

- Bloating

- Burping after meals

- Acid reflux or heartburn

- Difficulty swallowing pills

- Nausea after taking supplements

- Prolonged fullness after eating

- Undigested food in stool

Hypochlorhydria has been associated with many abnormal stomach conditions, including acute and chronic gastritis, autoimmune gastritis, GERD, peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. How is this possible? Let’s start by looking at the various functions of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. Then we will take a closer look at the mechanisms involved in each of these common stomach conditions.

The Functions of Hydrochloric Acid

The Functions of Hydrochloric Acid

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) functions in a variety of ways in the human body. Why is it that the use of acid-suppressing medications, such as PPIs, is associated with such a wide range of side effects, such as increased risk of vitamin and mineral deficiencies, increased food allergies, GI bacterial infection and osteoporosis-related bone fractures?[87-89] This is directly related to the functions of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. Hydrochloric acid has three very important functions in the stomach:

- Protein digestion (the breakdown of proteins into peptides and amino acids)

- Protection against bacterial infection (ie: H. pylori)

- Absorption of nutrients (some nutrients require sufficient HCl for proper absorption)

Protein Digestion

Protein Digestion

Most protein digestion takes place in the stomach in the presence of hydrochloric acid and pepsin. As discussed above, proteins are broken down into peptides and amino acids prior to absorption. The body needs a large pool of peptides and amino acids in order to build important tissue, such as muscle and bone and signaling agents such as hormones and neurotransmitters for the brain. If the substrates of these products are not available, they cannot be synthesized in adequate amounts. It’s really that simple.

Medications that suppress acid production have been associated with increased food allergies, presumably by decreasing gastric protein digestion and increasing sensitization.

“By increasing the gastric pH, they (acid-suppressing medications) interfere substantially with the digestive function of the stomach, leading to persistence of labile food protein during gastric transit. Indeed, both murine and human studies reveal that antiulcer medication increases the risk of food allergy induction. Thus anti-ulcer agents impeding gastric protein digestion have a major effect on the sensitization and effector phase of food allergy.”[90]

“By increasing the gastric pH, they (acid-suppressing medications) interfere substantially with the digestive function of the stomach, leading to persistence of labile food protein during gastric transit. Indeed, both murine and human studies reveal that antiulcer medication increases the risk of food allergy induction. Thus anti-ulcer agents impeding gastric protein digestion have a major effect on the sensitization and effector phase of food allergy.”[90]

Protein digestion is particularly important in the elderly who are at higher risk of sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass).

“It is known that the amino acids, including branched chain amino acids (BCAAs), are necessary for the maintenance of muscle health in the elderly. Food intake stimulates muscle protein synthesis, resulting in a positive protein balance.”[91]

“It is known that the amino acids, including branched chain amino acids (BCAAs), are necessary for the maintenance of muscle health in the elderly. Food intake stimulates muscle protein synthesis, resulting in a positive protein balance.”[91]

“Increasing protein intake in elderly and especially in frail elderly (higher than the recommended 0.8g/kg body weight per day) can minimize the sarcopenic process. Higher protein intake is associated with a significant decrease in lean mass in the elderly.”[92]

Protection Against Pathogenic Infection

Protection Against Pathogenic Infection

“Gastric acid plays an important part in the prevention of bacterial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract.”[93]

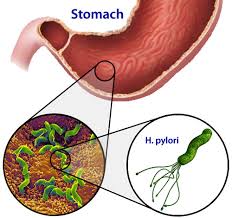

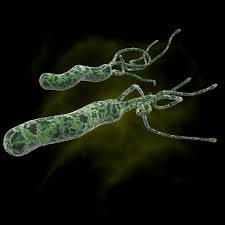

Adequate stomach acid is important not only for digestion but equally important in protecting against pathogenic organisms entering the stomach, small intestines and blood circulation.[94] The high acidity of the stomach due to hydrochloric acid inhibits the growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria and prevents them from inoculating the gastrointestinal tract, such as Helicobacter pylori. In other words, high stomach acidity acts as a barrier against pathogenic organisms and prevents them from inhabiting the stomach and small intestine. This barrier function of the stomach is referred to as the “gastric acid barrier” in the literature.

“The presence of profuse bacterial flora, including coliforms, found in markedly acid-deficient but not in normal stomachs, correlates well with the absence of bactericidal activity. Thus, the ‘gastric bactericidal barrier’ is primarily pH-hydrochloric acid dependent, with other constituents of gastric juice contributing little, if any, detectable effect on the destruction of microorganisms.”[94]

“The presence of profuse bacterial flora, including coliforms, found in markedly acid-deficient but not in normal stomachs, correlates well with the absence of bactericidal activity. Thus, the ‘gastric bactericidal barrier’ is primarily pH-hydrochloric acid dependent, with other constituents of gastric juice contributing little, if any, detectable effect on the destruction of microorganisms.”[94]

Low stomach acid (a condition called hypochlorhydria) is associated with increased levels of H. pylori infection, an increase in small intestinal pH (decreased acidity), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.[95] One study showed that 82% of patients with acute gastritis and hypochlorydria had H. pylori infection within 12 months of diagnosis vs. only 29% in a control group.[96]

The quantity of bacteria in the stomach has been shown to increase when acid secretion is inhibited by acid-suppressing medication, such as PPIs, the standard treatment for GERD.[97] In addition, low stomach acid predisposes the person to infection with a broad range of organisms.

The quantity of bacteria in the stomach has been shown to increase when acid secretion is inhibited by acid-suppressing medication, such as PPIs, the standard treatment for GERD.[97] In addition, low stomach acid predisposes the person to infection with a broad range of organisms.

“Reduction of gastric acid secretion predisposes to infection with a variety of organisms including those responsible for typhoid and non-typhoid salmonellosis, bacillary dysentery, cholera, brucellosis, giardiasis and strongyloidiasis. In addition, there are isolated reports to suggest that Clostridium difficile infection leading to pseudomembranous colitis, and infection with the fish tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum are more likely in association with hypochlorhydria.”[97]

Nutrient Absorption

Nutrient Absorption

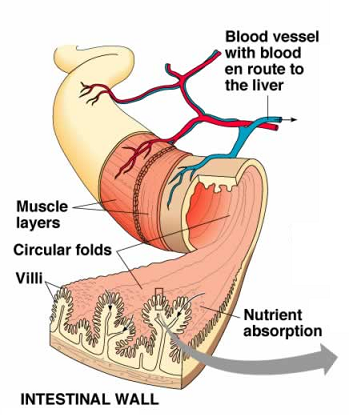

Another important function of gastric acid is to enhance nutrient absorption. Hypochlorhydria has been associated with decreased absorption of various vitamins and minerals including calcium, and increased risk of osteoporosis.[98] Low stomach acid secretion, which is common in gastric bypass surgeries, also leads to poor digestion and hence poor absorption of vitamin B12 into the body.

“Our observations implicate an inadequate release (maldigestion) of dietary vitamin B12 as the cause for the malabsorption in these patients, confirming the requirement for acid/peptic-mediated liberation of dietary vitamin B12 for subsequent absorption.”[99]

There is abundant evidence in the literature linking long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and decreased nutrient absorption. In addition to calcium and vitamin B12 absorption, there is concern over the absorption of other important minerals such as iron and magnesium as well.[100] We will take a closer look at these risks of PPIs commonly used in the treatment of GERD and acid reflux in a later section.

Causes of Hypochlorhydria

What leads to this condition of low stomach acid we have been discussing in so much detail? There are a number of causes and risk factors of this condition, including H. pylori infection, chronic stress and use of acid-suppressing medications. Increasing age is another risk factor. Let’s look at how each of these factors contributes to hypochlorhydria.

“H. pylori infection is a major cause of hypochlorhydria and has a major role in the progression from gastritis to atrophy and finally to gastric cancer. H. pylori and the associated changes in the stomach alter the ecological niche inhabited by the gastric microbiota.”[101]

H. pylori is a bacteria that can infect the stomach causing gastritis (inflammation of stomach lining) and hypochlorhydria. This happens due to the bacteria inducing a strong inflammatory response in the gastric lining and significantly inhibiting acid secretion by the parietal cells of the stomach.[102] Chronic H. pylori infection is considered the main cause of peptic ulcers and can progress to atrophic gastritis, dysplasia (a precancerous condition) and then to stomach cancer.[103] H. pylori infection has also been associated with autoimmune gastritis.[104]

H. pylori infection is extremely common and affects approximately 50% of the world’s population.[105] However, only 15% of those infected with H. pylori develop disease, and pathogenesis depends upon strain virulence, host genetic susceptibility, and environmental cofactors.[106] Additionally, hypochlorhydria predisposes to H. pylori infection, therefore hypochlorhydria and chronic H. pylori infections can become a vicious cycle. It is not uncommon for people to have recurrent H. pylori infections after being treated with antibiotics while their hypochlorhydria condition is never addressed.

Hypochlorydria can result from short or long-term use of PPI medications as these medications have powerful acid-suppressing effects.

“PPIs are associated with several adverse events mechanistically linked to hypochlorhydria. Emerging data illustrate the potential risks associated with both short-and long-term PPI therapy, including Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea, community-acquired pneumonia, osteoporotic fracture, vitamin B12 deficiency, and inhibition of antiplatelet therapy.”[107]

Researchers now believe that these medications are being over-prescribed in various medical settings and putting many patients at increased risk of various side-effects.

“The effectiveness of PPIs has led to overutilization in multiple treatment arenas, exposing patients to an increasing number of potential risks.”[108]

Chronic psychological stress has significant impacts on the physiology of the gut and has been linked to alterations in gastrointestinal motility, changes in enzyme secretion, increase in intestinal permeability and negative effects on the regenerative capacity of the intestinal mucosa, mucosal blood flow and intestinal microbiota.[109,110]

Treatment of Hypochlorhydria in Functional Medicine

As you can see, having low levels of stomach acid can put you at risk of having a wide range of health problems, such as various pathogenic GI infections, including H. pylori, a number of nutrient absorption problems, (such as vitamin B12, calcium, iron and magnesium) and increased risk of osteoporosis and bone fractures. As we will see in a later section, it is also associated with a condition known as intestinal permeability or “leaky gut”. Fortunately, it is a condition that is easily managed by supplementing with stomach enzymes, such as betaine HCl and pepsin, which help to increase gastric acidity. This is an extremely common problem with a simple solution that is often overlooked in conventional medicine.  Betaine HCl supplementation has also been shown to normalize stomach acidity in patients on long-term PPI therapy and improve absorption of other medications without any noticeable side-effects.[111]

Betaine HCl supplementation has also been shown to normalize stomach acidity in patients on long-term PPI therapy and improve absorption of other medications without any noticeable side-effects.[111]

“Maintaining adequate gastric pH ensures a sufficient sterilizing barrier against enteric pathogens, allows for proper absorption of micronutrients, preserves normal intestinal permeability and prevents hypergastrinemia…therefore, maintaining adequate gastric pH might be a preventive measure. Supplemental HCl has been shown to reduce (acidify) gastric pH in subjects with simulated hypochlorhydria.”[112]

Gastritis

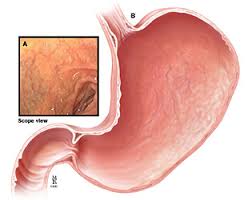

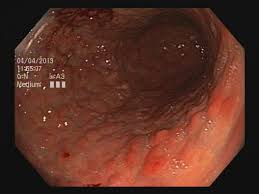

Gastritis is a condition of inflammation of the stomach lining. It is usually diagnosed by biopsy via upper GI endoscopy in which a tube is inserted through the oral cavity and through the esophagus and into the stomach and a tissue sample is removed and examined. Sometimes it can be visualized through endoscopy and no tissue sample is needed. Redness or swelling indicate inflammation or irritation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection is considered the most common cause of gastritis. The second most common cause of gastritis is the use of PPI (proton-pump inhibitor) medications. Another common cause of gastritis is the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and aspirin, which can irritate the stomach lining and lead to gastric ulcers and bleeding.[113]

Gastritis is a condition of inflammation of the stomach lining. It is usually diagnosed by biopsy via upper GI endoscopy in which a tube is inserted through the oral cavity and through the esophagus and into the stomach and a tissue sample is removed and examined. Sometimes it can be visualized through endoscopy and no tissue sample is needed. Redness or swelling indicate inflammation or irritation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection is considered the most common cause of gastritis. The second most common cause of gastritis is the use of PPI (proton-pump inhibitor) medications. Another common cause of gastritis is the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and aspirin, which can irritate the stomach lining and lead to gastric ulcers and bleeding.[113]

“H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis, which is asymptomatic in the majority of carriers but is considered a major risk factor for the development of gastric and duodenal ulcers and the two gastric malignancies (cancers).”[114]

“H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis, which is asymptomatic in the majority of carriers but is considered a major risk factor for the development of gastric and duodenal ulcers and the two gastric malignancies (cancers).”[114]

“H. pylori is now accepted as the major cause for gastritis and gastric cancer. Numerous investigations for the pathogenesis of H. pylori have been done. Antibiotic treatment for H. pylori has been such a controversial issue that it is still not well established as to who should be treated. The high ‘recurrence rate’, potential long term complications, and socioeconomic usefulness of the bactericidal treatment have been disputed.”[115]

Other Causes of Gastritis: PPIs and NSAIDs

Other Causes of Gastritis: PPIs and NSAIDs

A recent large-scale study showed that over 20% of gastritis patients did not have H. pylori infection. Among those patients, a majority of them (almost 70%) had a history of PPI medication use.[113] Animal studies have suggested that long-term PPI use can lead to gastric inflammation, possibly through microbial overgrowth.[116] Another common cause of gastritis is the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Almost half of the patients with H. pylori-negative gastritis were either past or current NSAID users.[113] As we will learn in the section devoted to the small intestine, NSAID use causes damage not only to the stomach but to the intestines as well. In fact, the damage is greater to the small intestines than to the stomach.[117]

“…long-term administration of NSAIDs causes adverse gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including mucosal lesions, bleeding, peptic ulcer, and inflammation in intestine leading to perforation, strictures in small and large intestines, leading to chronic problems. Some of the adverse effects of NSAIDs may be asymptotic, but in many cases there are reports of life-threatening incidents.”[118]

“…long-term administration of NSAIDs causes adverse gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including mucosal lesions, bleeding, peptic ulcer, and inflammation in intestine leading to perforation, strictures in small and large intestines, leading to chronic problems. Some of the adverse effects of NSAIDs may be asymptotic, but in many cases there are reports of life-threatening incidents.”[118]

Atrophic Gastritis

Atrophic Gastritis

Atrophic gastritis (AG) is a stomach condition that is characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa with loss of gastric glandular cells and replacement by intestinal-type epithelium and fibrous tissue. Atrophy of the gastric mucosa is the endpoint of chronic gastritis. It has been associated with two primary causes: chronic Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and autoimmunity directed against gastric glandular cells, called autoimmune gastritis.[119] Patients with AG have a high risk for developing gastric cancer. Since stomach acid production decreases with age, the prevalence of atrophic gastritis is increased in people over age 60. [120]

“Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is well known to be associated with the development of precancerous lesions such as chronic atrophic gastritis (AG), or gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and cancer.”[121]

Autoimmune Gastritis

Autoimmune Gastritis

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is an organ-specific autoimmune disease, in which inflammation of the mucosa of the gastric body results in total loss of gastric glands and achlorhydria (non-acid production or severe hypochlorhydria). AIG patients typically have parietal cell antibodies which aid diagnosis. In many, but not all AIG patients, vitamin B12 absorption is deficient, which leads to pernicious anemia.[122] Vitamin B12 deficiency is common in the elderly who often suffer from B12 malabsorption. Approximately 15%-20% of vitamin B12 malabsorption in elderly patients is due to pernicious anemia, which results from elevated antibodies against intrinsic factor (IF), which is necessary for vitamin B12 absorption.[123] As in atrophic gastritis, there is evidence of chronic H. pylori infection playing a role in the development of autoimmune gastritis.

“Signs of H. pylori infection in autoimmune gastritis, and positive autoimmune serum markers in H. pylori gastritis suggest an etiological role for H. pylori in autoimmune gastritis.”[123]

“Signs of H. pylori infection in autoimmune gastritis, and positive autoimmune serum markers in H. pylori gastritis suggest an etiological role for H. pylori in autoimmune gastritis.”[123]

In addition to gastric parietal cell antibodies, there is also evidence of a connection between H. pylori infection and TPO antibodies against the thyroid.

“Results of this study support the idea of a connection between infection of H. pylori and the occurrence of anti-TPO autoantibodies representing thyroid autoimmunity and gastric parietal cells autoantibodies representing the thyrogastric syndrome.”[124]

In the next segment, we will continue to examine common disorders of the stomach, focusing on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In subsequent segments in this series, we will examine common disorders that result from dysfunction of the small intestine and colon.

References

86. E Husebye, V Skar, T Høverstad, K Melby. Fasting hypochlorhydria with gram positive gastric flora is highly prevalent in healthy old people. Gut. 1992 October; 33(10): 1331–1337.

87. Tetsuhide Ito, Robert T. Jensen. Association of Long-term Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy with Bone Fractures and effects on Absorption of Calcium, Vitamin B12, Iron, and Magnesium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1. Published in final edited form as: Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 December; 12(6): 448–457. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0141-0

88. Laura E. Targownik, Lisa M. Lix, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008 August 12; 179(4): 319–326. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071330

89. Joel J. Heidelbaugh, Kathleen L. Goldberg, John M. Inadomi. Adverse Risks Associated With Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2009 October; 5(10): 725–734.

90. Eva Untersmayr, Erika Jensen-Jarolim. The role of protein digestibility and antacids on food allergy outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 December 9. Published in final edited form as: J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 June; 121(6): 1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.025

91. Mariangela Rondanelli, Milena Faliva, et al. Novel Insights on Nutrient Management of Sarcopenia in Elderly. Biomed Res Int. 2015; 2015: 524948. Published online 2015 January 29. doi: 10.1155/2015/524948

92. Y. Rolland, S. Czerwinski, et al. Sarcopenia: Its Assessment, Etiology, Pathogenesis, Consequences And Future Perspectives. J Nutr Health Aging. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 April 16. Published in final edited form as: J Nutr Health Aging. 2008 Aug-Sep; 12(7): 433–450.

93. Yoshihisa Urita, Toshiyasu Watanabe, et al. Extensive Atrophic Gastritis Increases Intraduodenal Hydrogen Gas. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2008; 2008: 584929. Published online 2008 June 16. doi: 10.1155/2008/584929

94. R. A. Giannella, S. A. Broitman, N. Zamcheck. Gastric acid barrier to ingested microorganisms in man: studies in vivo and in vitro. Gut. 1972 April; 13(4): 251–256.

95. Kassarjian Z, Russell RM. Hypochlorhydria: a factor in nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1989;9:271-285.

96. W Harford, C Barnett, E Lee, G Perez-Perez, M Blaser, W Peterson. Acute gastritis with hypochlorhydria: report of 35 cases with long term follow up. Gut. 2000 October; 47(4): 467–472. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.467

97. C W Howden, R H Hunt. Relationship between gastric secretion and infection. Gut. 1987 January; 28(1): 96–107.

98. Sipponen P, Härkönen M. Hypochlorhydric stomach: a risk condition for calcium malabsorption and osteoporosis? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(2):133-8. doi: 10.3109/00365520903434117. Review.

99. C D Smith, S B Herkes, K E Behrns, V F Fairbanks, K A Kelly, M G Sarr. Gastric acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption after vertical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1993 July; 218(1): 91–96.

100. Tetsuhide Ito, Robert T. Jensen. Association of Long-term Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy with Bone Fractures and effects on Absorption of Calcium, Vitamin B12, Iron, and Magnesium. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 December 1. Published in final edited form as: Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010 December; 12(6): 448–457. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0141-0

101. Alexander Sheh, James G Fox. The role of the gastrointestinal microbiome in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Gut Microbes. 2013 November 1; 4(6): 505–531. Published online 2013 August 19. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26205

102. Arindam Saha, Charles E Hammond, Craig Beeson, Richard M Peek, Jr, Adam J Smolka. Helicobacter pylori represses proton pump expression and inhibits acid secretion in human gastric mucosa. Gut. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 November 14.

103. Smolka AJ, Backert S. How Helicobacter pylori infection controls gastric acid secretion. J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jun;47(6):609-18. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0592-1. Epub 2012 May 8. Review.

104. Lea Irene Veijola, Aino Mirjam Oksanen, Pentti Ilmari Sipponen, Hilpi Iris Kaarina Rautelin. Association of autoimmune type atrophic corpus gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 January 7; 16(1): 83–88. Published online 2010 January 7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i1.83

105. Traci L Testerman, James Morris. Beyond the stomach: An updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 September 28; 20(36): 12781–12808. Published online 2014 September 28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12781

106. Atherton JC. The pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastro-duodenal diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:63–96.

107. Joel J. Heidelbaugh, Kathleen L. Goldberg, John M. Inadomi. Adverse Risks Associated With Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterol Hepatol. (N Y) 2009 October; 5(10): 725–734.

108. Joel J. Heidelbaugh, Andrea H. Kim, Robert Chang, Paul C. Walker. Overutilization of proton-pump inhibitors: what the clinician needs to know. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012 July; 5(4): 219–232. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12437358

109. Konturek PC1, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011 Dec;62(6):591-9.

110. Bhatia V1, Tandon RK. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Mar;20(3):332-9.

111. Marc Anthony R. Yago, Adam R. Frymoyer, et al. Gastric Re-acidification with Betaine HCl in Healthy Volunteers with Rabeprazole-Induced Hypochlorhydria. Mol Pharm. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 March 8. Published in final edited form as: Mol Pharm. 2013 November 4; 10(11): 4032–4037.

112. Jonathan E. Prousky. Cobalamin deficiency in elderly patients. CMAJ. 2005 February 15; 172(4): 450–451. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041424

113. Helena Nordenstedt, David Y. Graham, et al. Helicobacter pylori-Negative Gastritis: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Am J Gastroenterol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 April 12.

114. Salama NR, Hartung ML, Müller A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013 Jun; 11(6):385-99.

115. Inchul Lee. Critical pathogenic steps to high risk Helicobacter pylori gastritis and gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 June 7; 20(21): 6412–6419. Published online 2014 June 7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6412

116. Zavros Y, Rieder G, Ferguson A, et al. Genetic or chemical hypochlorhydria is associated with inflammation that modulates parietal and G-cell populations in mice. Gastroenterol. 2002;122:119–33.

117. John L Wallace. Mechanisms, prevention and clinical implications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-enteropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 March 28; 19(12): 1861–1876. Published online 2013 March 28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1861

118. Mau Sinha, Lovely Gautam, et al. Current Perspectives in NSAID-Induced Gastropathy Mediators Inflamm. 2013; 2013: 258209. Published online 2013 March 12. doi: 10.1155/2013/258209

119. Yan-Cheng Dai, Zhi-Peng Tang, Ya-Li Zhang. How to assess the severity of atrophic gastritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 April 7; 17(13): 1690–1693. Published online 2011 April 7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1690

120. Saltzman JR, Russell RM. The aging gut: nutritional issues. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:309-324.

121. Jiro Watari, Nancy Chen, et al. Helicobacter pylori associated chronic gastritis, clinical syndromes, precancerous lesions, and pathogenesis of gastric cancer development.

World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 14; 20(18): 5461–5473. Published online 2014 May 14. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5461

122. Aino Mirjam Oksanen, Katri Eerika Haimila, Hilpi Iris Kaarina Rautelin, Jukka Antero Partanen. Immunogenetic characteristics of patients with autoimmune gastritis.

World J Gastroenterol. 2010 January 21; 16(3): 354–358. Published online 2010 January 21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.354

123. Lea Irene Veijola, Aino Mirjam Oksanen, Pentti Ilmari Sipponen, Hilpi Iris Kaarina Rautelin. Association of autoimmune type atrophic corpus gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 January 7; 16(1): 83–88. Published online 2010 January 7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i1.83

124. Sterzl I1, Hrdá P, Matucha P, Cerovská J, Zamrazil V. Anti-Helicobacter Pylori, anti-thyroid peroxidase, anti-thyroglobulin and anti-gastric parietal cells antibodies in Czech population. Physiol Res. 2008;57 Suppl 1:S135-41. Epub 2008 Feb 13.