“The future of healthcare will be focused on, not anti-aging research, but genomic protection with lifestyle medicine” Jeffrey Bland, Ph.D.

Have you ever noticed that some people look young for their age? Have you seen people that look much older than they actually are? Why is that? Are there internal mechanisms in the body that promote accelerated aging? If so, can we influence these mechanisms through our diet and lifestyle choices or are they genetically determined? Researchers are now studying the aging process in living organisms and the factors that influence those mechanisms that lead to accelerated aging and the degenerative diseases of aging, such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, autoimmune disease, dementias and cancer.

What researchers are finding is that these mechanisms that are driving these disease processes are largely related to diet and lifestyle choices and environmental factors. Genetics alone plays a much smaller role in one’s risk of developing most degenerative diseases than previously believed. It is estimated that only 10% of the chronic diseases seen in the U.S. (heart disease, diabetes and arthritis) which occur in the adult populations have a significant genetic component.(1) There are genetic diseases but in 90% of all chronic disease, it is the interaction between diet, lifestyle and environmental factors on our genes that determine health or disease development. The focus of this research is ultimately aimed at identifying these mechanisms that lead to accelerated aging and how these mechanisms can be slowed down through dietary and lifestyle choices. This is the concept of biological aging.

What researchers are finding is that these mechanisms that are driving these disease processes are largely related to diet and lifestyle choices and environmental factors. Genetics alone plays a much smaller role in one’s risk of developing most degenerative diseases than previously believed. It is estimated that only 10% of the chronic diseases seen in the U.S. (heart disease, diabetes and arthritis) which occur in the adult populations have a significant genetic component.(1) There are genetic diseases but in 90% of all chronic disease, it is the interaction between diet, lifestyle and environmental factors on our genes that determine health or disease development. The focus of this research is ultimately aimed at identifying these mechanisms that lead to accelerated aging and how these mechanisms can be slowed down through dietary and lifestyle choices. This is the concept of biological aging.

Delaying the Degenerative Diseases of Aging

Delaying the Degenerative Diseases of Aging

Bruce Ames, Ph.D., is a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at U.C. Berkeley. He has been studying the aging process for over 4 decades. His research focuses on cancer and aging and he has authored over 500 scientific publications. He is among the few hundred most-cited scientists in all fields. His focus has been on mitochondrial dysfunction and genomic stability and how these concepts affect biological aging. His research has shown that mitochondrial decay or dysfunction leads to accelerated aging and the degenerative diseases we see in the elderly. He has also pioneered the field of genomic stability (the ability to maintain the genome and prevent damage to the DNA). Damage to DNA is associated with many of the degenerative diseases associated with aging. Let’s take a closer look at what these fields of study are all about and what Dr. Ames’ and his colleagues’ research is showing.

For those that are interested in this topic, here is an interesting 30 min. video of Dr. Ames lecturing on the topic of delaying the degenerative diseases of aging: Bruce Ames, Ph.D. Lectures on Aging

The Mitochondria

The Mitochondria

“The mitochondria, often referred to as “the power house of the cell”, are the source of at least 90% of the energy generated in the cell. The majority of this energy (80%) is produced as ATP by oxidative phosphorylation. A single cell can contain from 200 to 2,000 mitochondria. The number of mitochondria in specific cell types varies considerably, although within a given cell type the number is closely regulated.” (2)

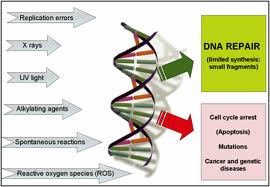

Mitochondria are the organelles of the cell that produce the majority of the body’s energy. Think of the mitochondria as the “energy-producing factories” of the body. This is where ATP is generated, which is the body’s energy “currency”. ATP is then used by the cells to fuel cellular processes. Oxygen “accepts” free electrons as part of cellular metabolism in the production of ATP. As a result of this process oxygen radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS) are formed which have the potential of causing damage to the mitochondria and the organelles of the cell, including the DNA. Fortunately, our bodies have an antioxidant system built in, which works to neutralize these free oxygen radicals and prevent damage to the cell (when they are provided with the necessary micronutrients).

Mitochondrial Decay

Mitochondrial Decay

Dr. Ames’ research found as the mitochondria age, they give out more and more oxygen radicals. These reactive oxygen species (ROS) are more prone to damage the mitochondria and the DNA as we age. Mitochondria are very vulnerable to oxidative damage. Increasing evidence is showing that mitochondrial decay drives the biological aging process. As the mitochondria become damaged, they are unable to produce ATP to fuel the cellular processes of other cells, tissues and organs. This leads to organ dysfunction and accelerated aging. Protecting ourselves against damage to the mitochondria and DNA is key to slowing down the aging process. Dr. Ames research has been focused on identifying nutrients in our diet that are necessary to prevent mitochondrial damage. We will take a look at these micronutrients that have been identified to slow down aging later in this series.

Genomic Stability

Genomic Stability

“The results of this study illustrate the strong impact of a wide variety of micronutrients and their interactions on genome health, depending upon their level of intake” Michael Fenech, Ph.D.

The genome (DNA where our genes are coded) is fairly stable but can become unstable under certain conditions of DNA damage. When DNA becomes damaged or defective, it is usually not a big problem. Again, our bodies have the capacity to repair damaged DNA when this occurs or “silence” genes which are defective so that DNA defects don’t continue to be replicated. The DNA repair ability of a cell is vital to the integrity of its genome and to its normal functioning and the functioning of the organism. This is the concept of genomic stability. However, this DNA repair system can become inadequate when DNA damage is excessive or when the micronutrients that are necessary for DNA repair are deficient. The replication of damaged or defective DNA leads to degenerative disease, according to Dr. Ames’ research. After his years of research, he has found, essentially, the reason why we are aging faster than we otherwise would, is because of our nutrient-deprived diets and consumption of low-quality food. We will see later that micronutrients play an important role in genomic stability. We will look at specific micronutrients that have been shown to protect the genome and delay or prevent the onset of degenerative disease later in this series. We will also take a look at the new field of nutrigenomics, which looks at how nutrients in food interact with our genes to produce healthy states or promote disease.

How do we know how fast we are aging biologically?

In part 2 of this series we will examine the characteristics and key biomarkers of biological aging. Stay tuned…

References

1. Weatherall DJ. 1985. The New Genetics and Clinical Practice, Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press

2. Lamson DW, Plaza SM. Mitochondrial factors in the pathogenesis of diabetes: A hypothesis for treatment. Alternative Medicine Review 2002;7(2):94-111